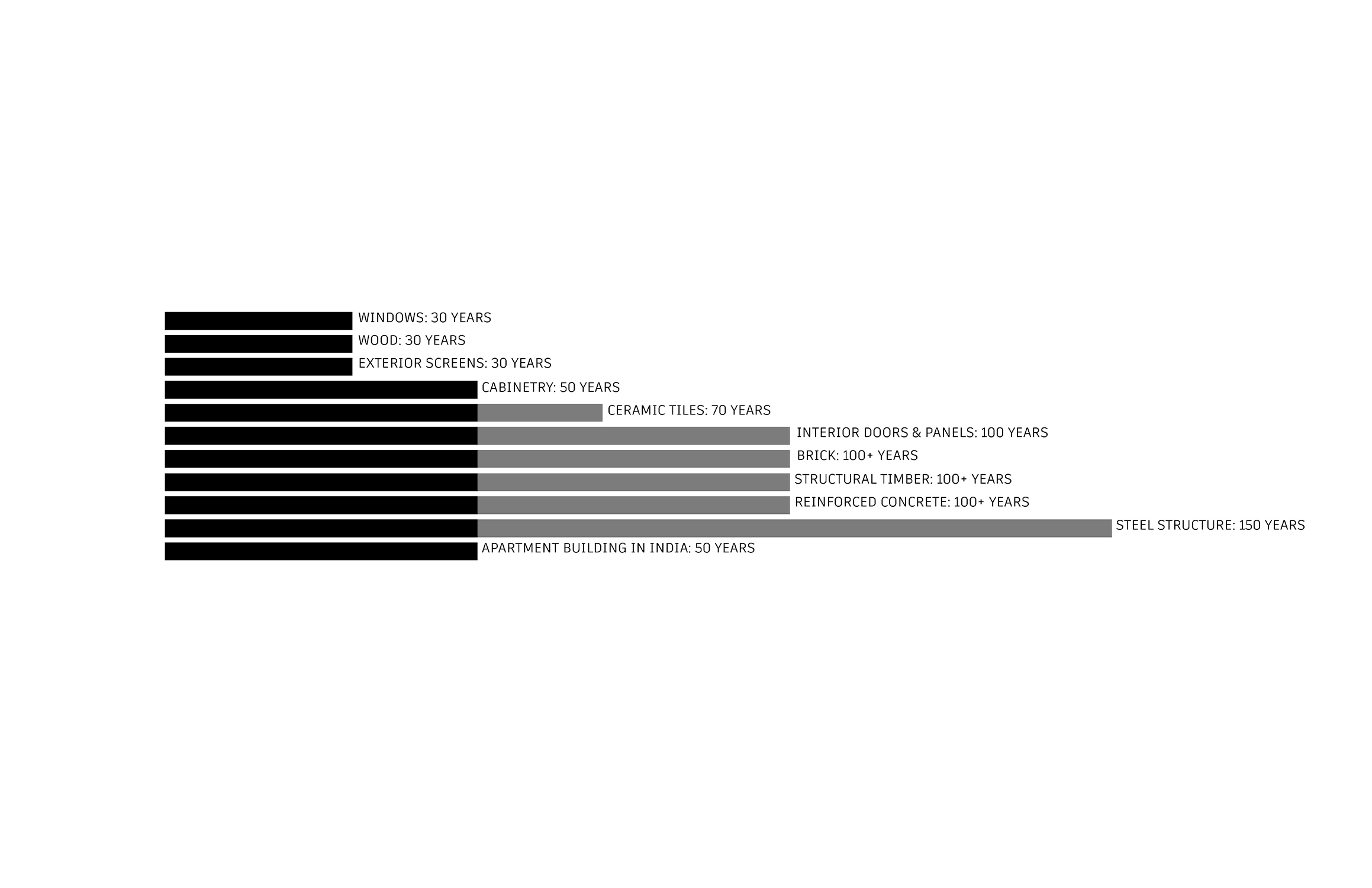

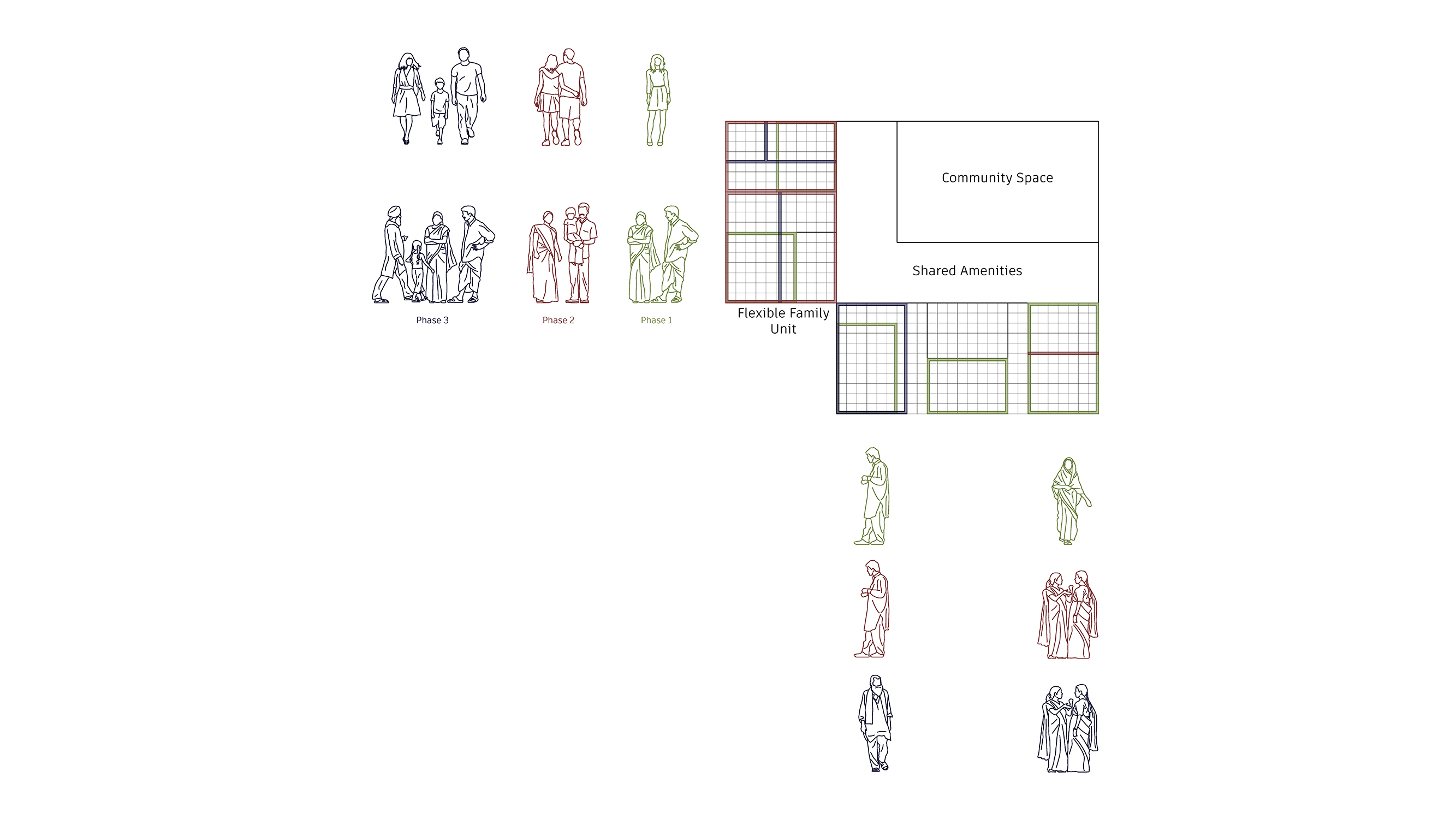

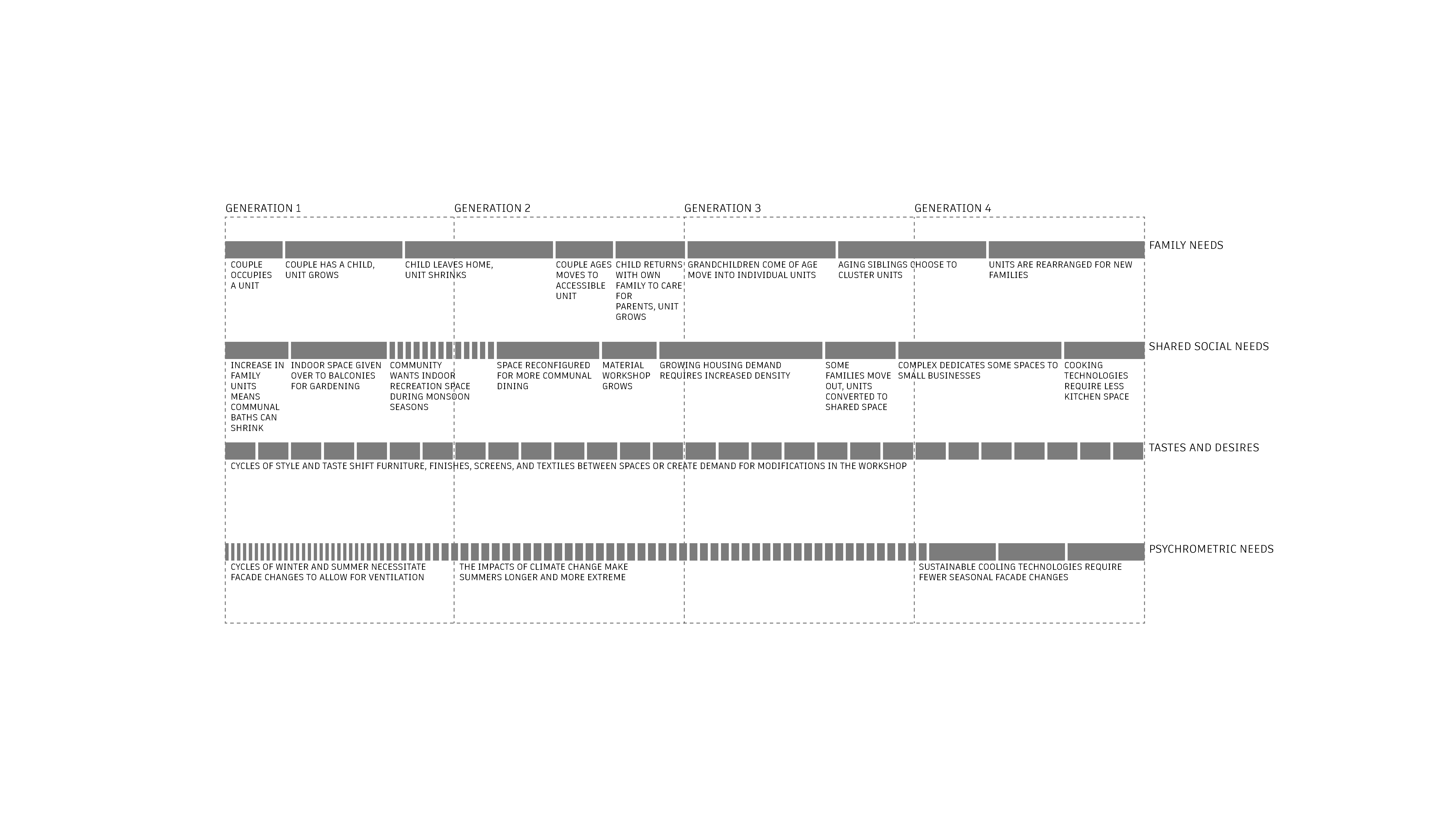

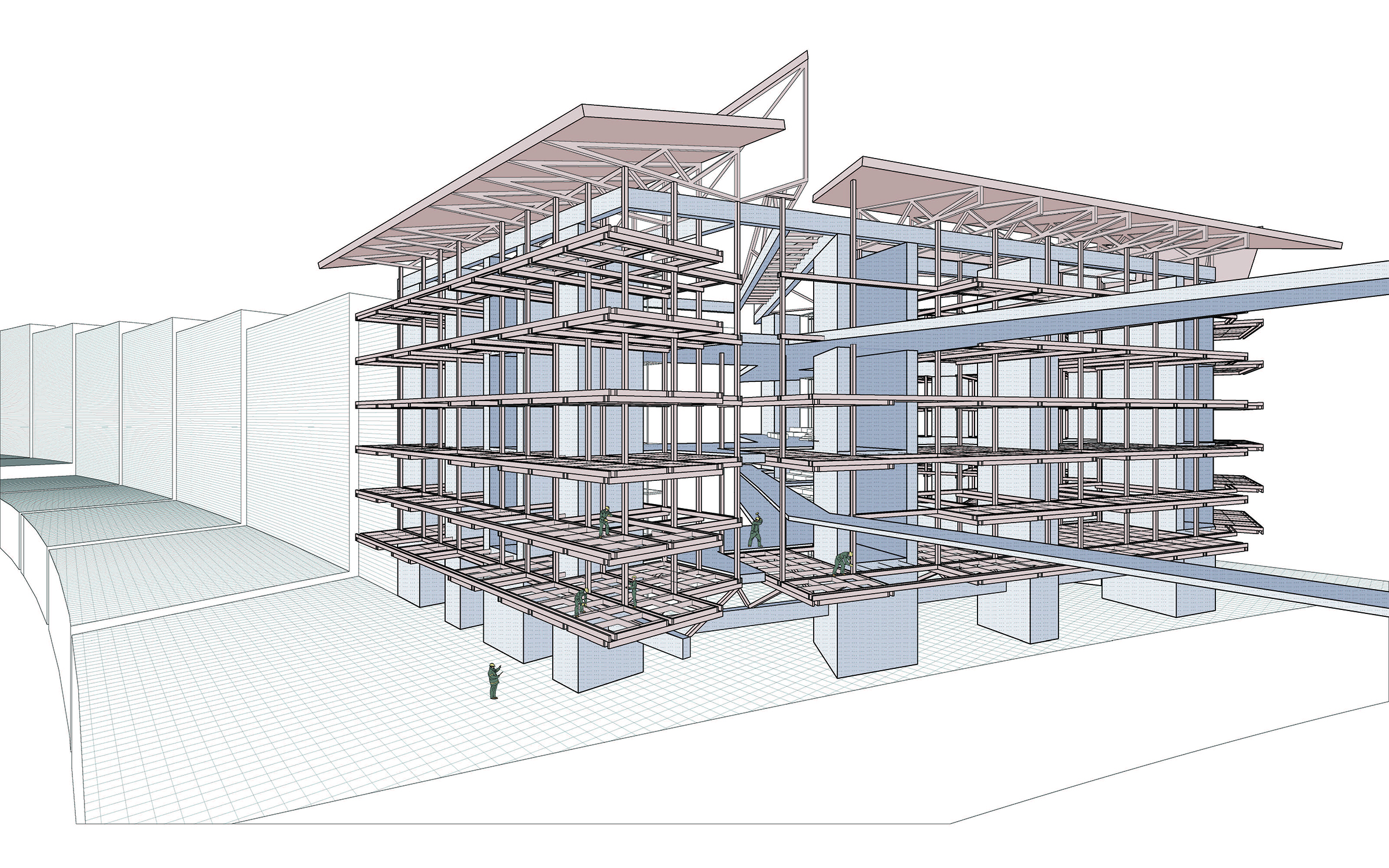

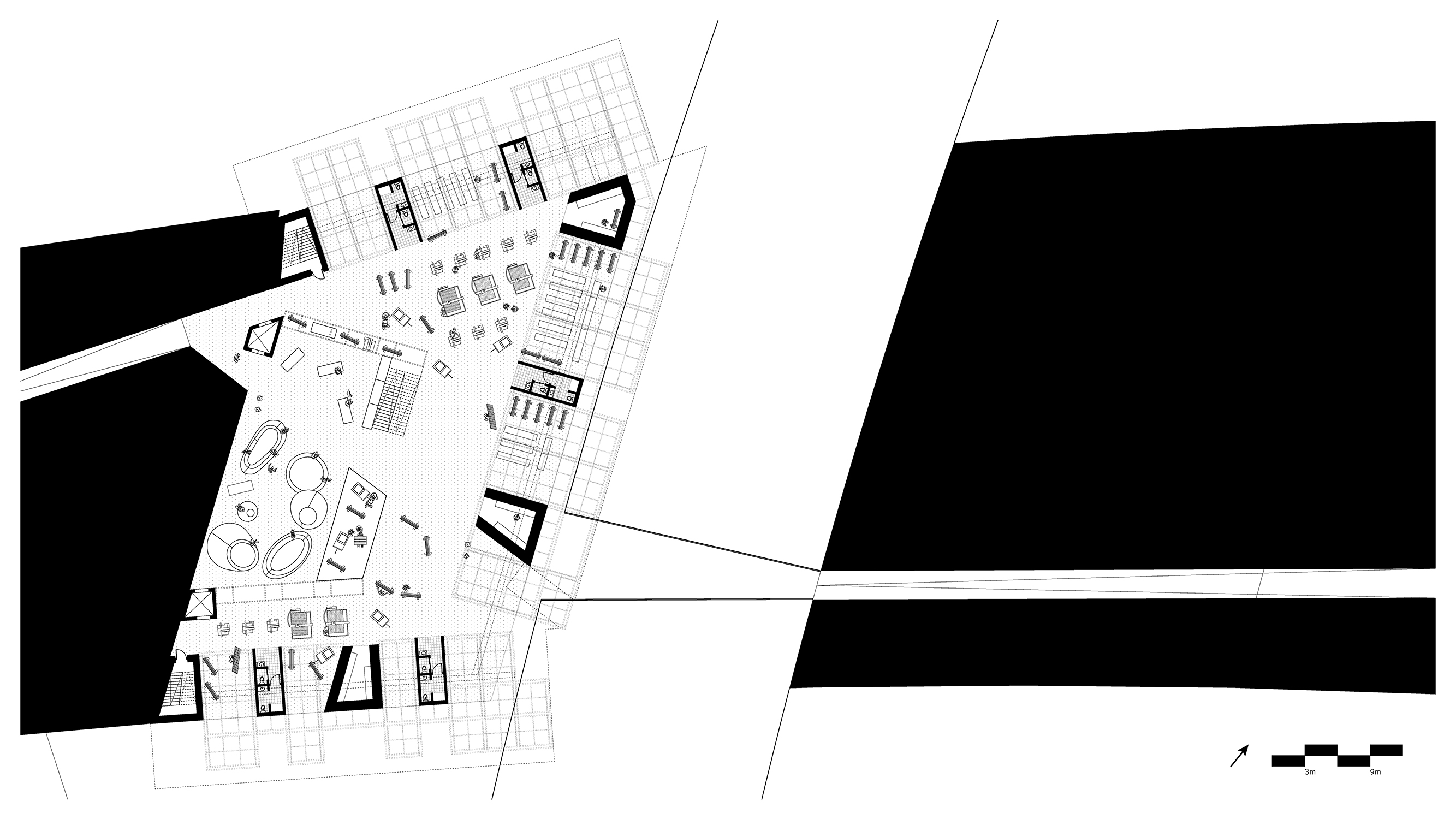

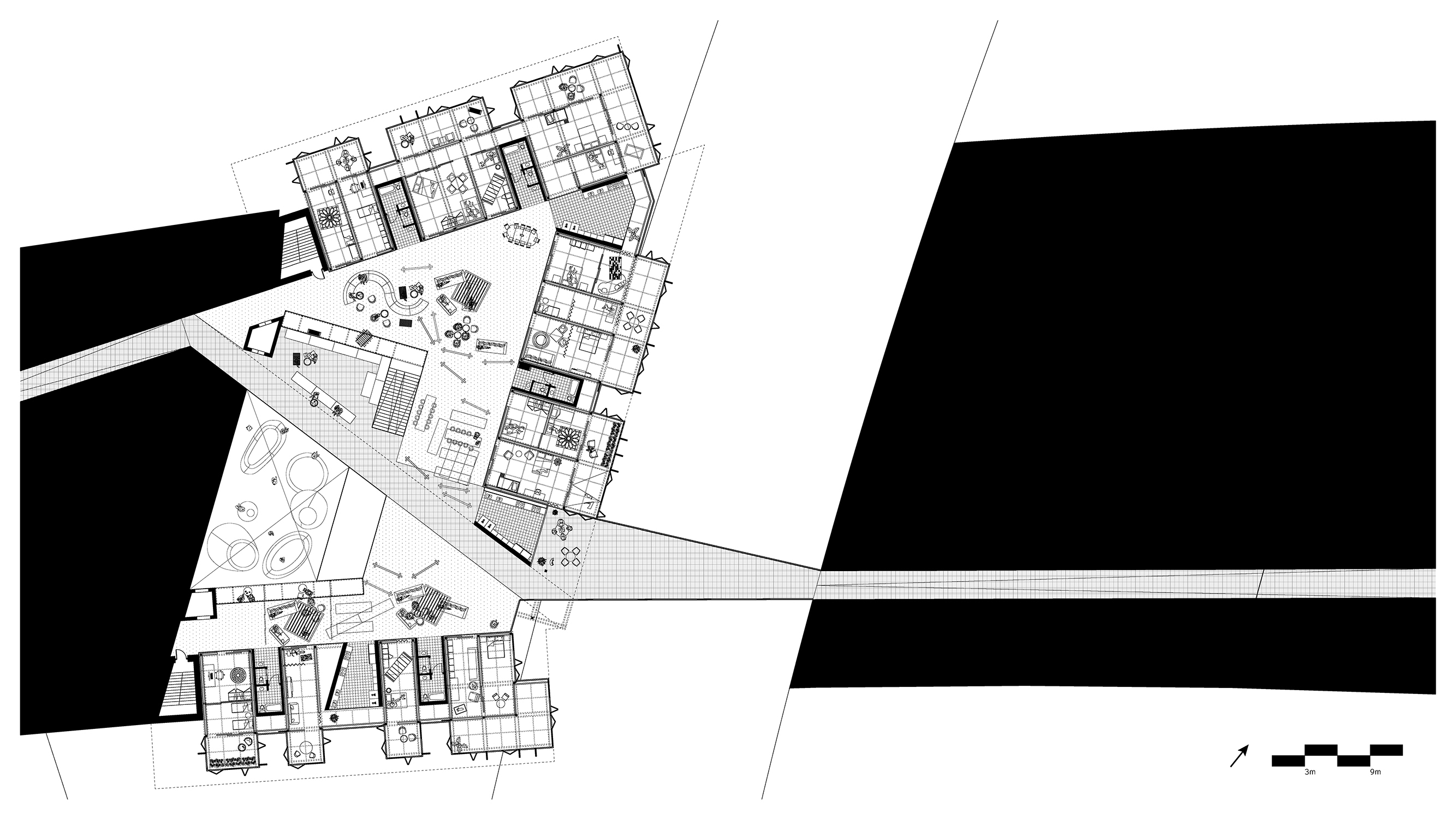

Commodified housing relies on an individual ownership model with fixed spatial and material boundaries. Static material boundaries tie all elements of a building to a single, market-driven lifespan and limit the material agency of future residents. Alternatively, this co-housing prototype seeks to extend material lifespans through circular use and promote flexible boundaries that eliminate permanent, private ownership of units. Through material commoning, this proposal restores occupants’ material agency and allows the building to be continuously renewed. An on-site material bank and workshop facilitates a community of craftsmen that experiment with flexible construction methods, primarily using continuously recycled wood products.

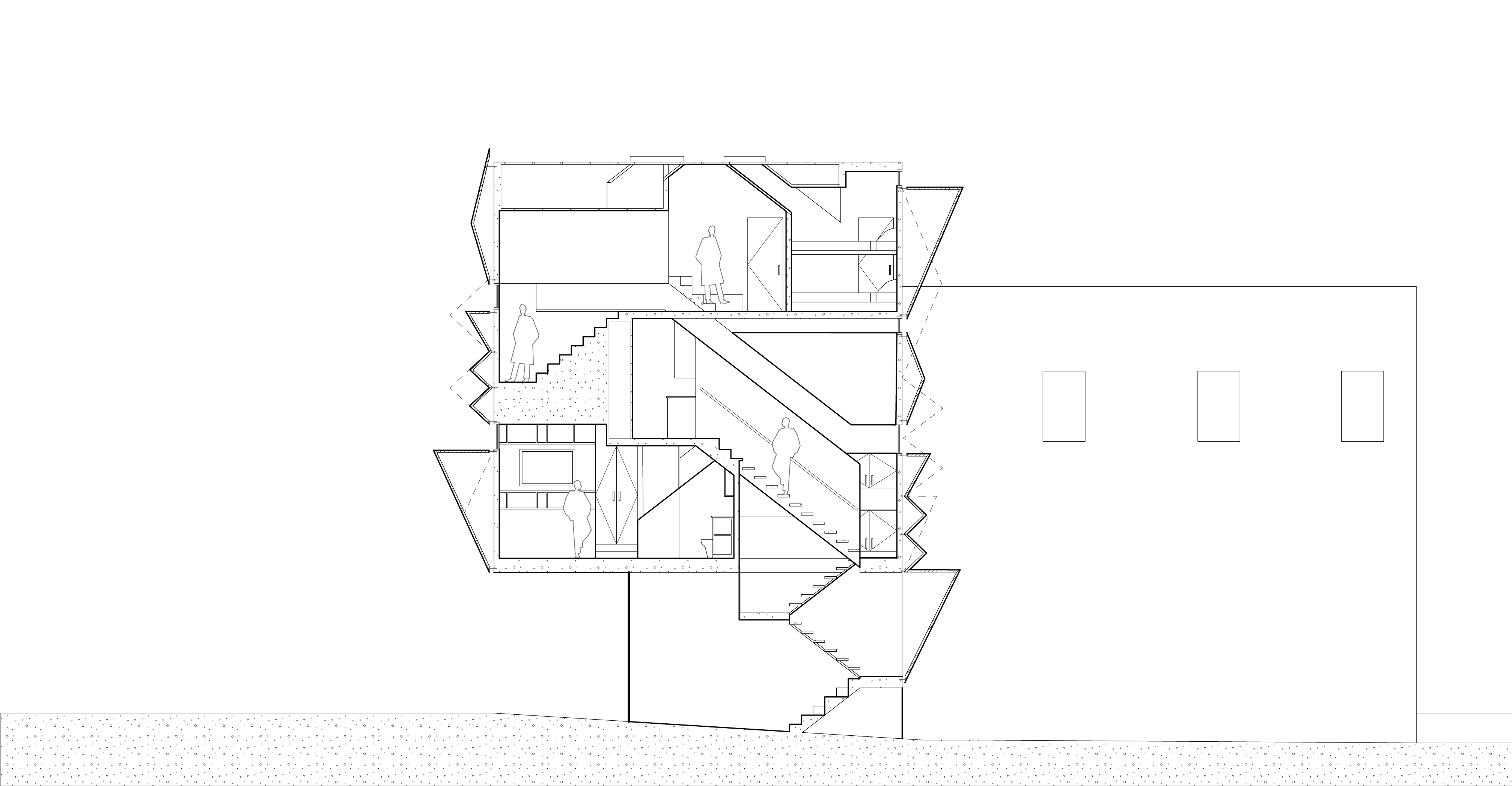

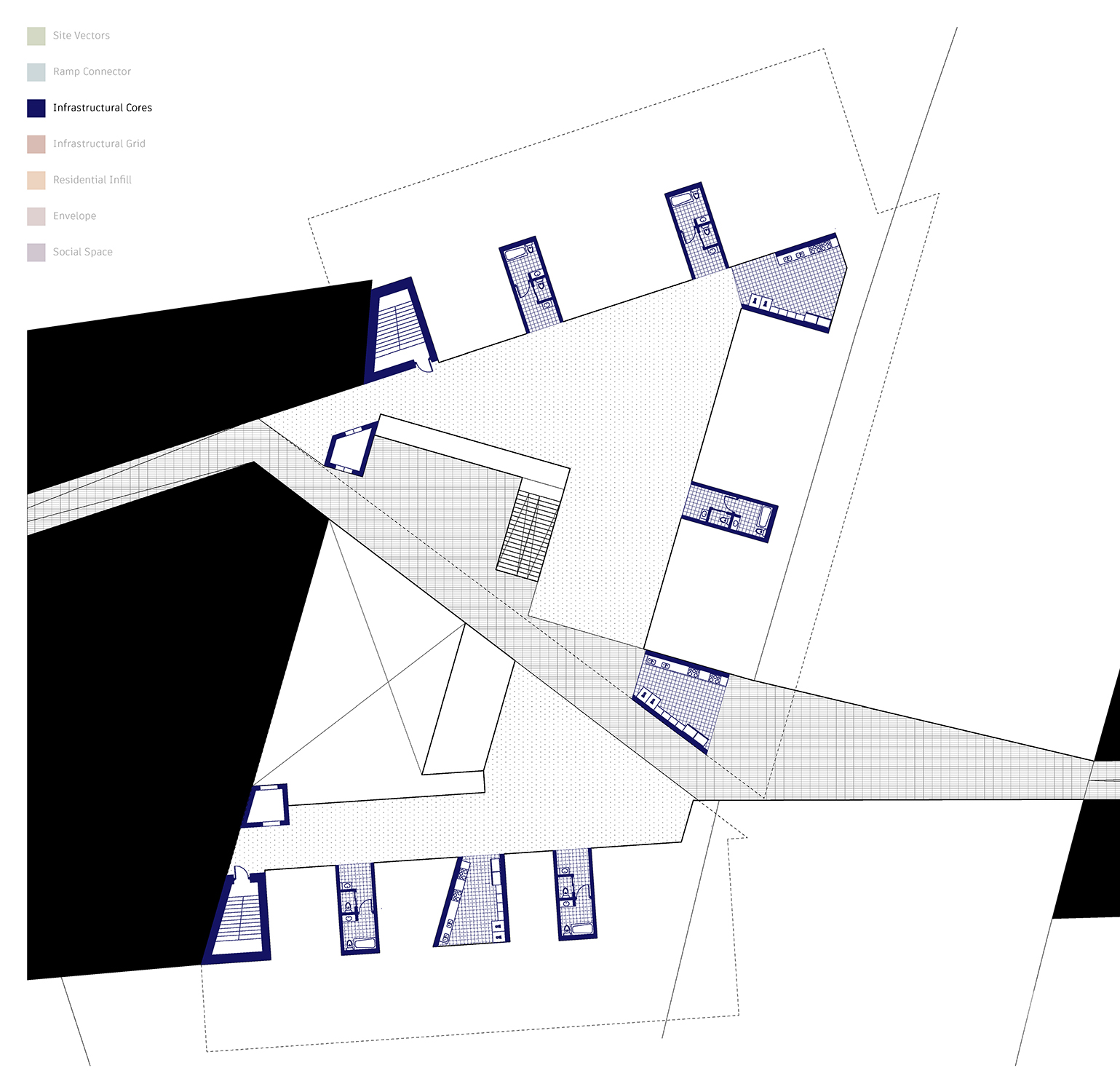

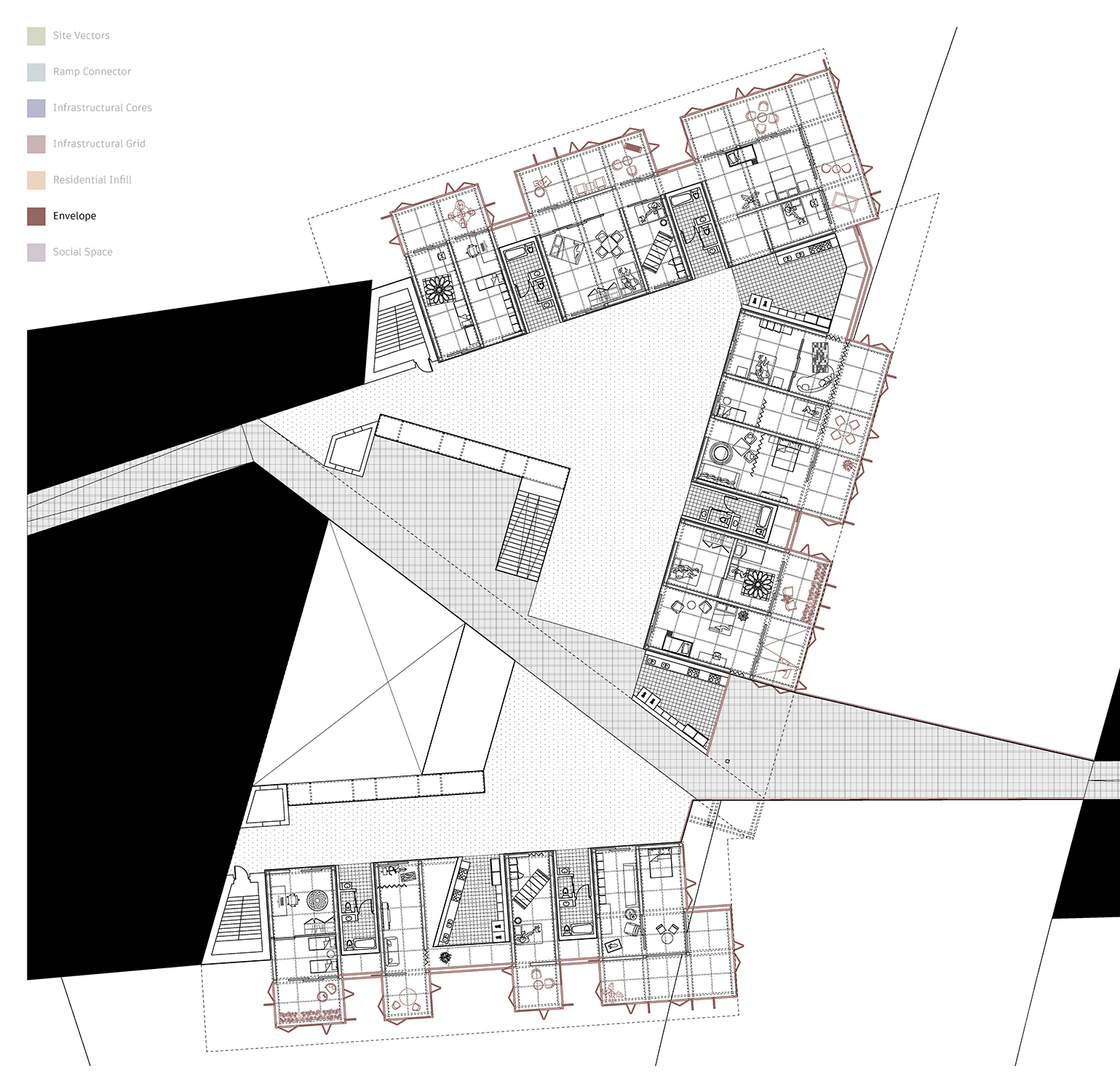

Through this material changeability,

the boundaries of individual units and shared spaces are regularly redefined within a fixed logic of modularity, structure, and systems.

Elements ranging from furniture to entire wall systems can be moved to

accommodate seasonal changes, growing families, or social activities.

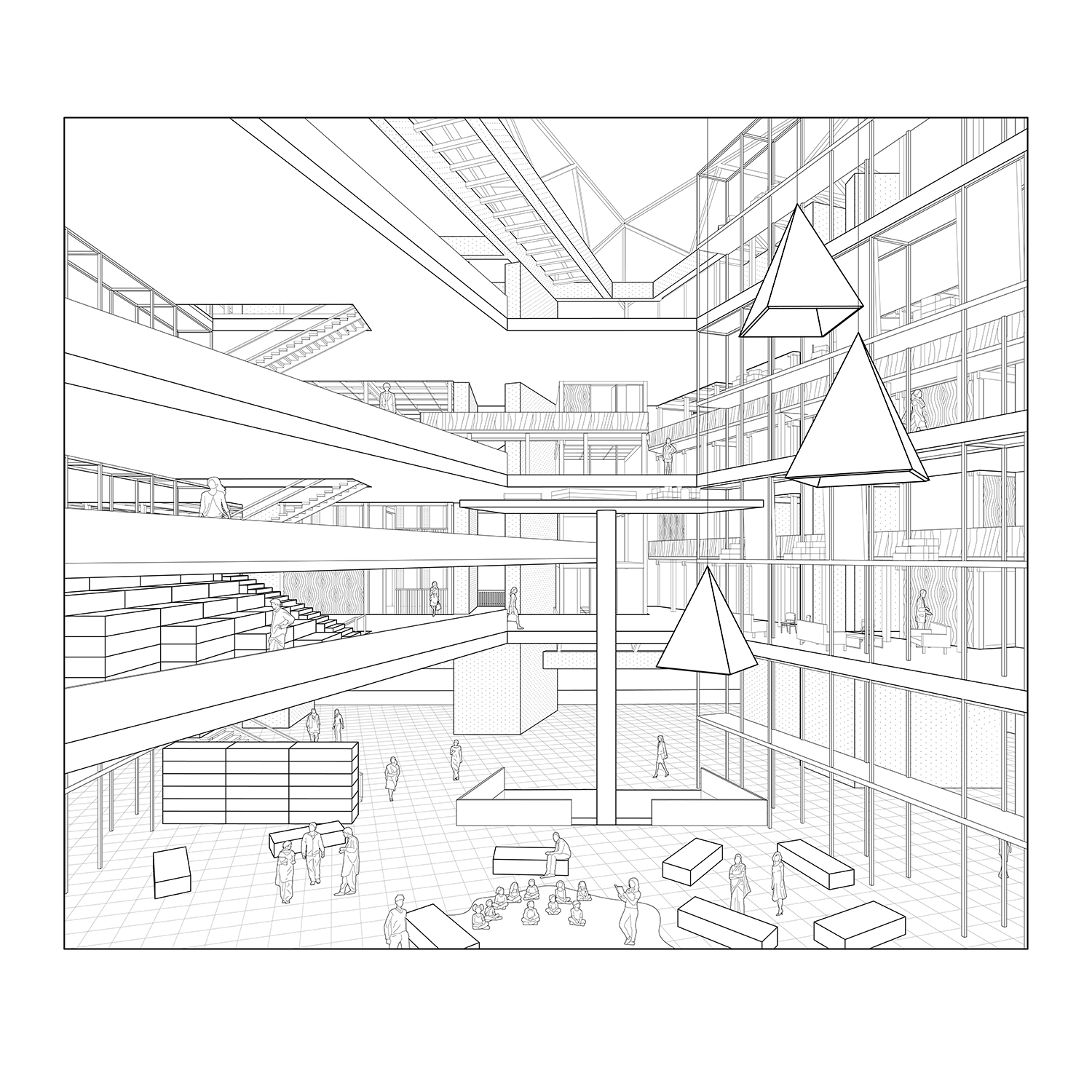

While the entire community shares material bank resources, clusters of

neighbors share cooking and bathing spaces. The community is organized

around a central public event atrium, which also acts as a connection point

between two Line of Goodwill pathways. The collective aspects of the prototype extend beyond its residents.

As Auroville grows, the city can look to the work done in this prototypical

community for new building construction concepts that promote sustainability, longevity, and co-ownership.

In collaboration with Andrew Economos Miller.

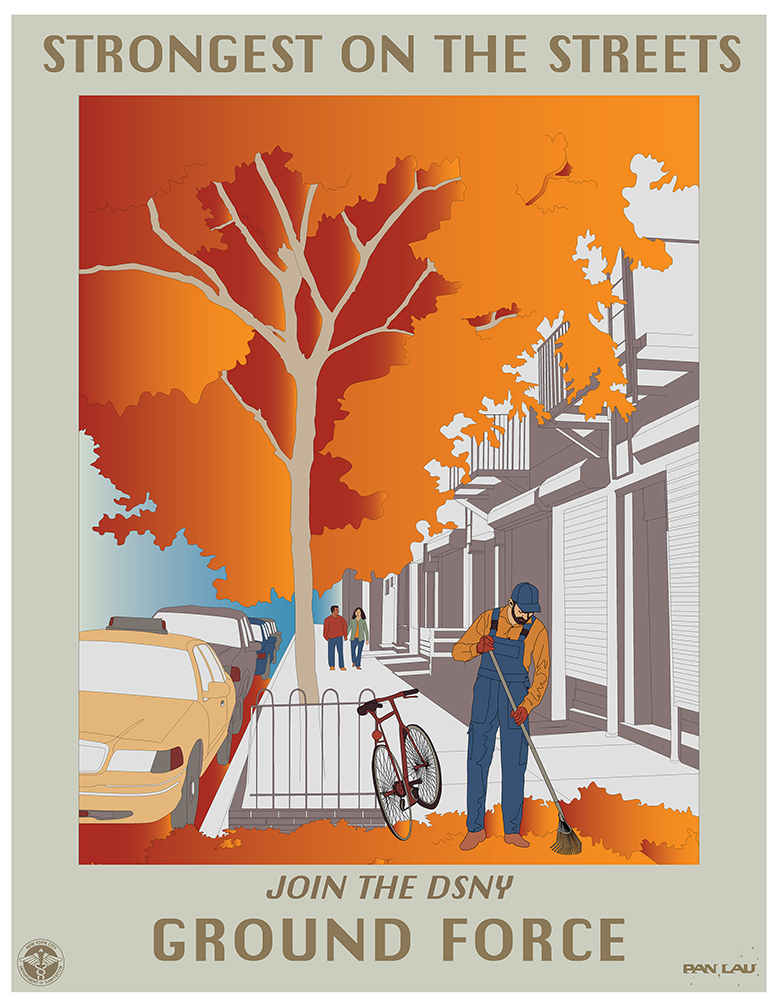

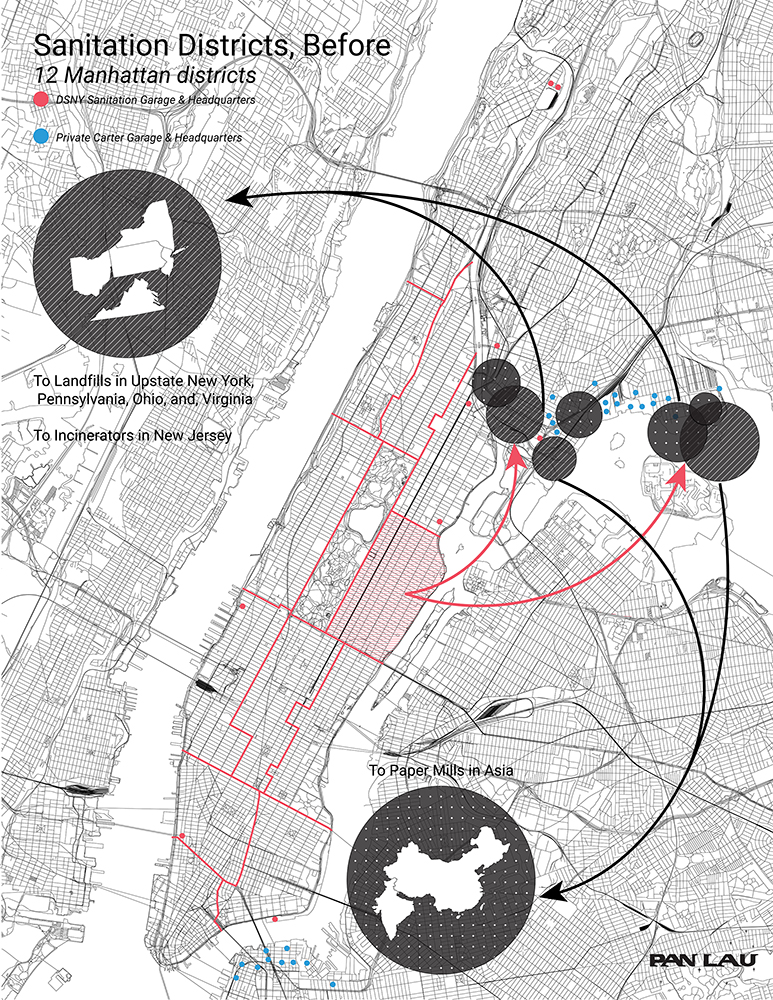

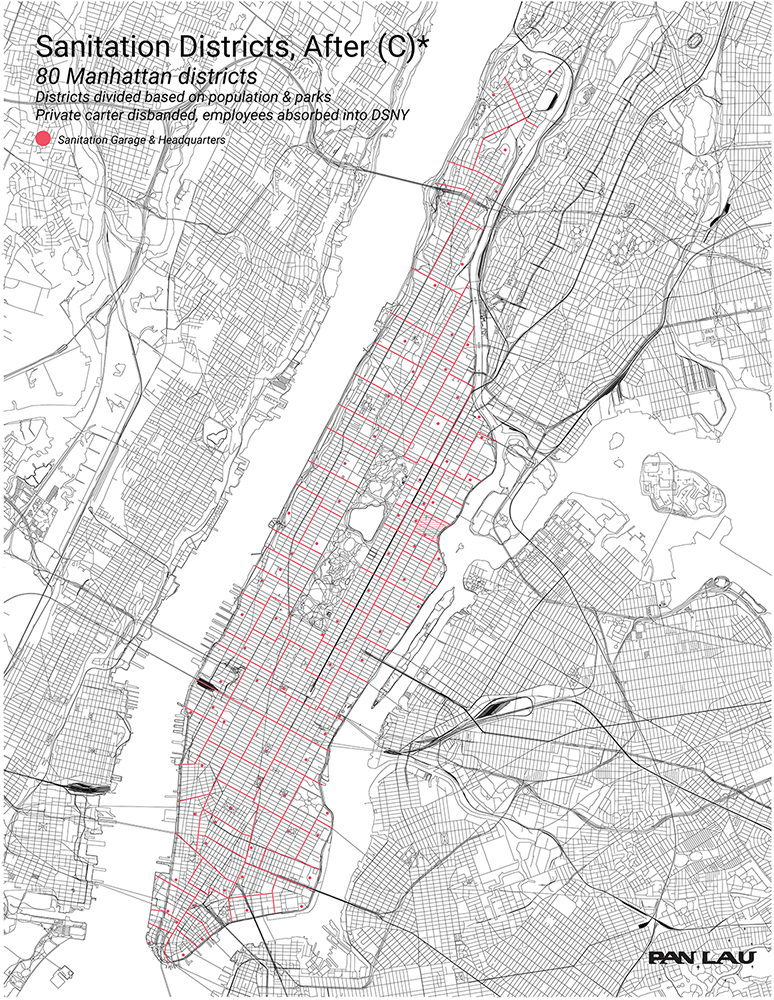

Designing Waste Culture Zero Waste Action Plan, New York City

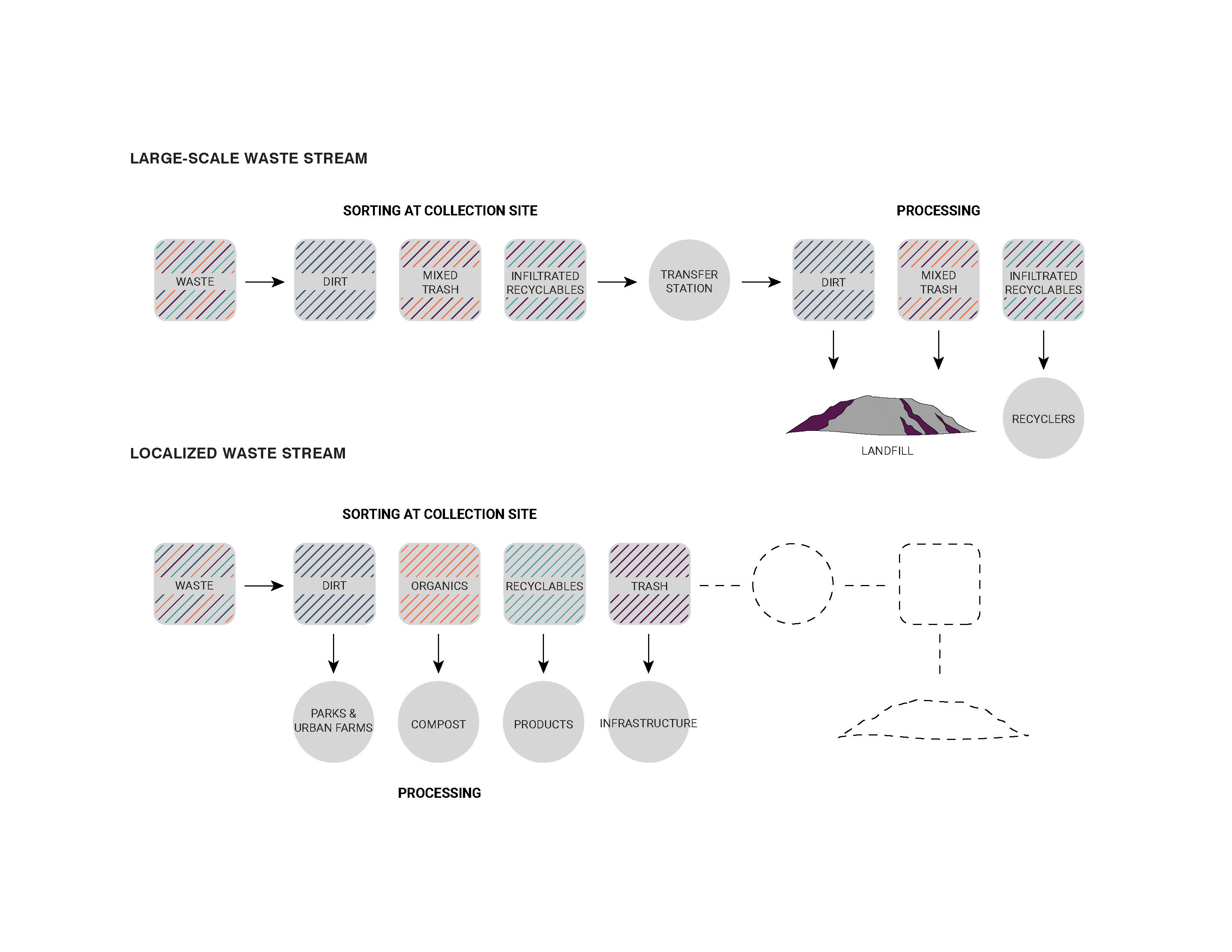

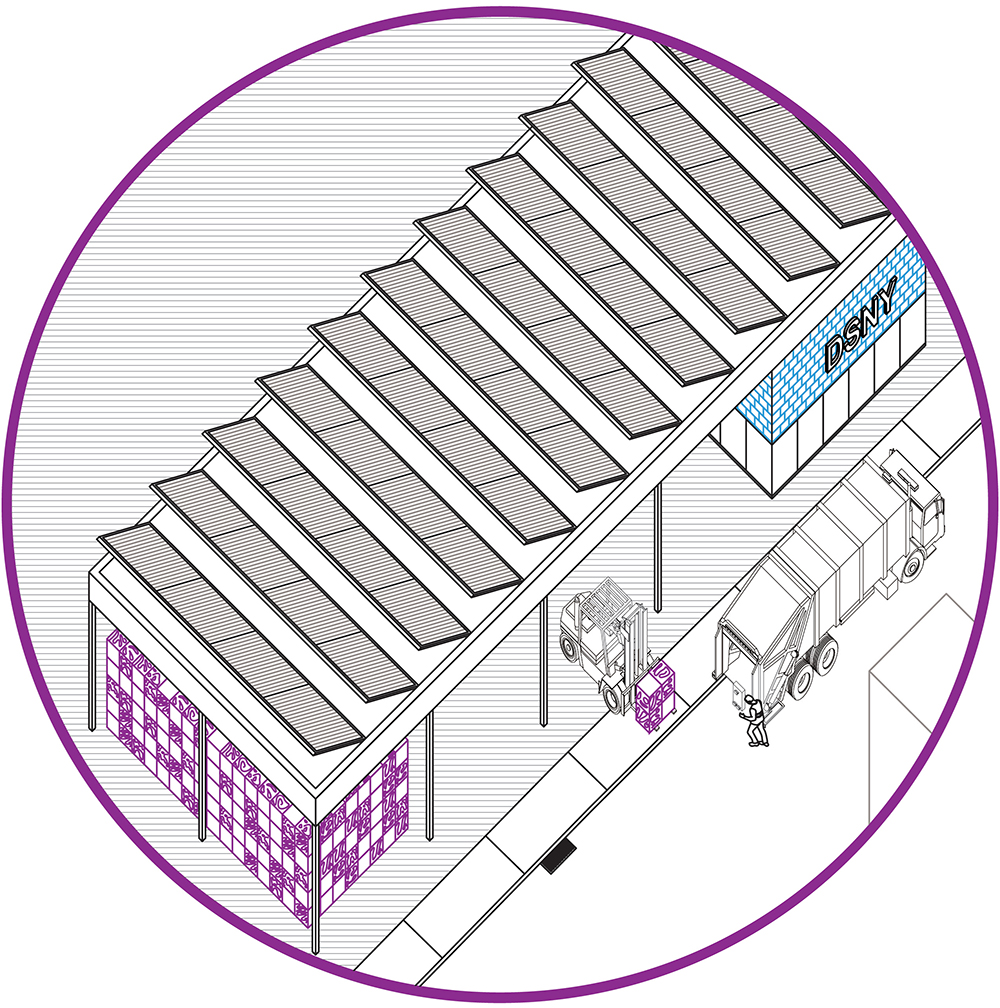

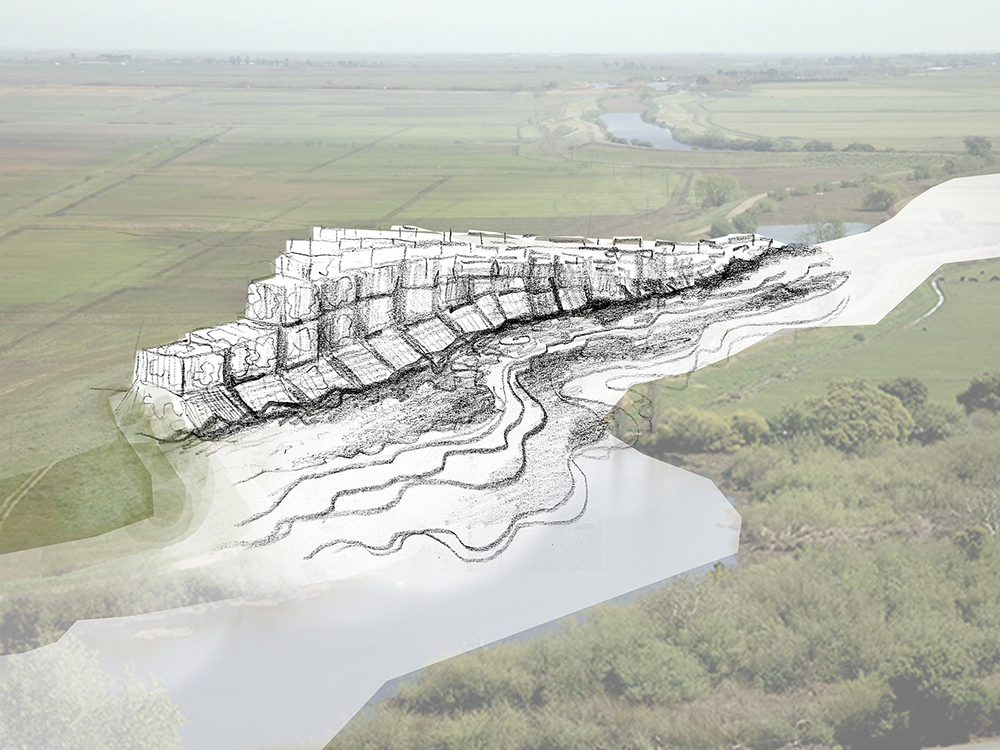

Currently, the New York Department of Sanitation (DSNY) collects 12,552 tons of residential trash each day. Over 200 private carters collect an equivalent amount of commercial trash, covering the city through inefficient and overlapping routes. These private carters are frequently accused of abusive labor practices and are responsible for nearly all of garbage truck related injuries and fatalities. Once waste is collected, it’s taken to transfer stations, primarily in Brooklyn and the South Bronx. From there, huge quantities of money, energy, and infrastructure go toward transporting waste great distances.

In most areas of NYC, waste is not dealt with in the neighborhood that produces it. The city has made attempts to increase waste sorting at a local level, but initiatives like the 2013 Organics Pilot Program have been largely unsuccessful due to lack of participation and education. Our proposal seeks to localize NYC’s waste sorting, collection, and management. By changing the way NYC interacts with its waste, we hope to change the way that NYC thinks about its waste. We believe that a change in waste culture, and an ultimate waste reduction, will have repercussions throughout NYC’s built environment, changing streetscapes, greenspaces, and infrastructure.

In collaboration with Christine Pan.

Terrace Hinge Restorative Justice Center, New London, Connecticut

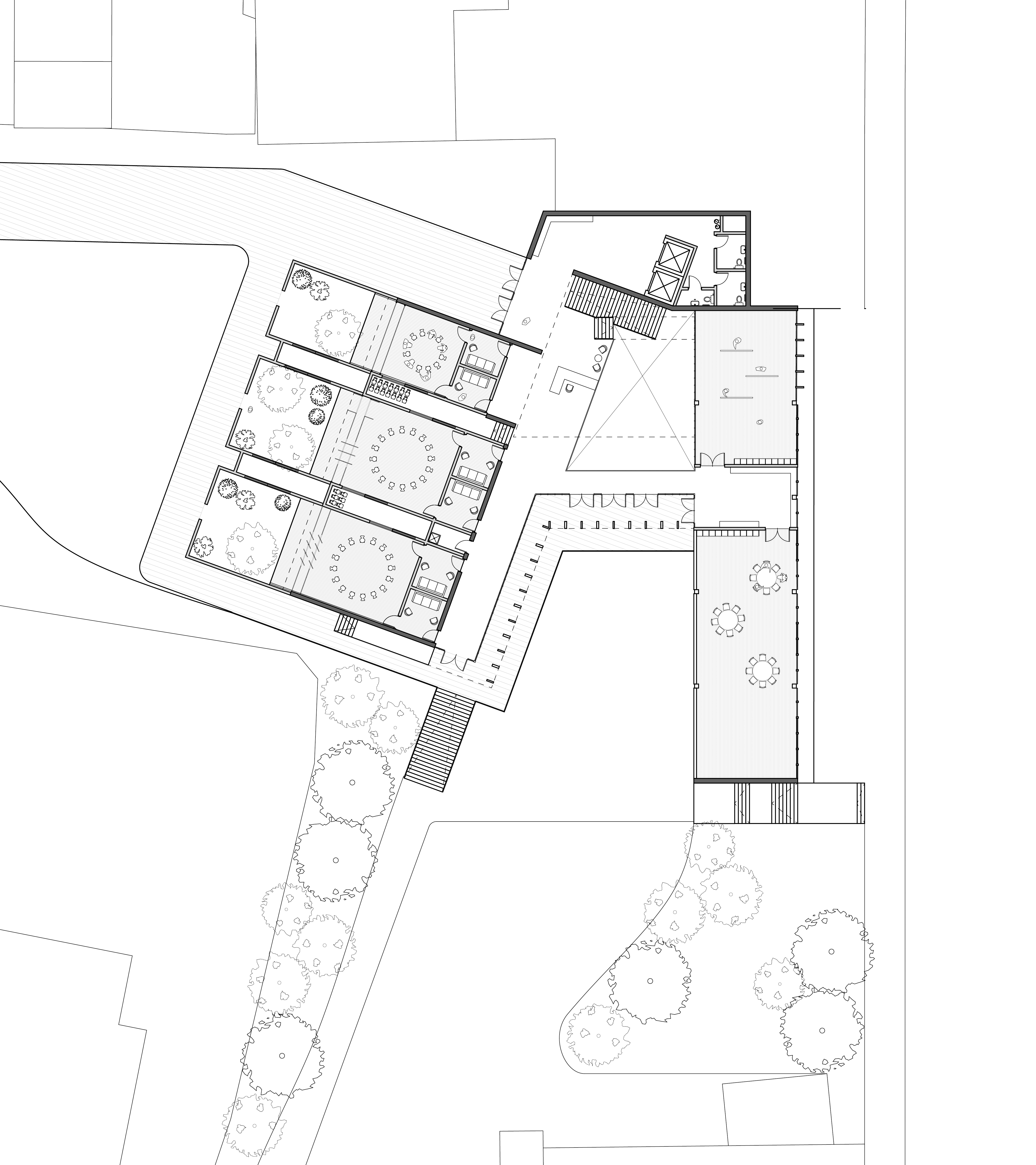

As an alternative to the traditional court system, restorative justice mediates discussion circles between victims and perpetrators in order to address harms rather than assign blame. This project nests restorative justice within a community center, making a statement that this type of conflict resolution is a public amenity.

The building is organized around three different areas of the site—the bottom, the middle, and the top of the hill, with a distinct entry, outdoor space, and program in each area. The different areas address community in varying ways; from an open public courtyard that connects to an interior atrium, to the more protected circle rooms which connect to private gardens.

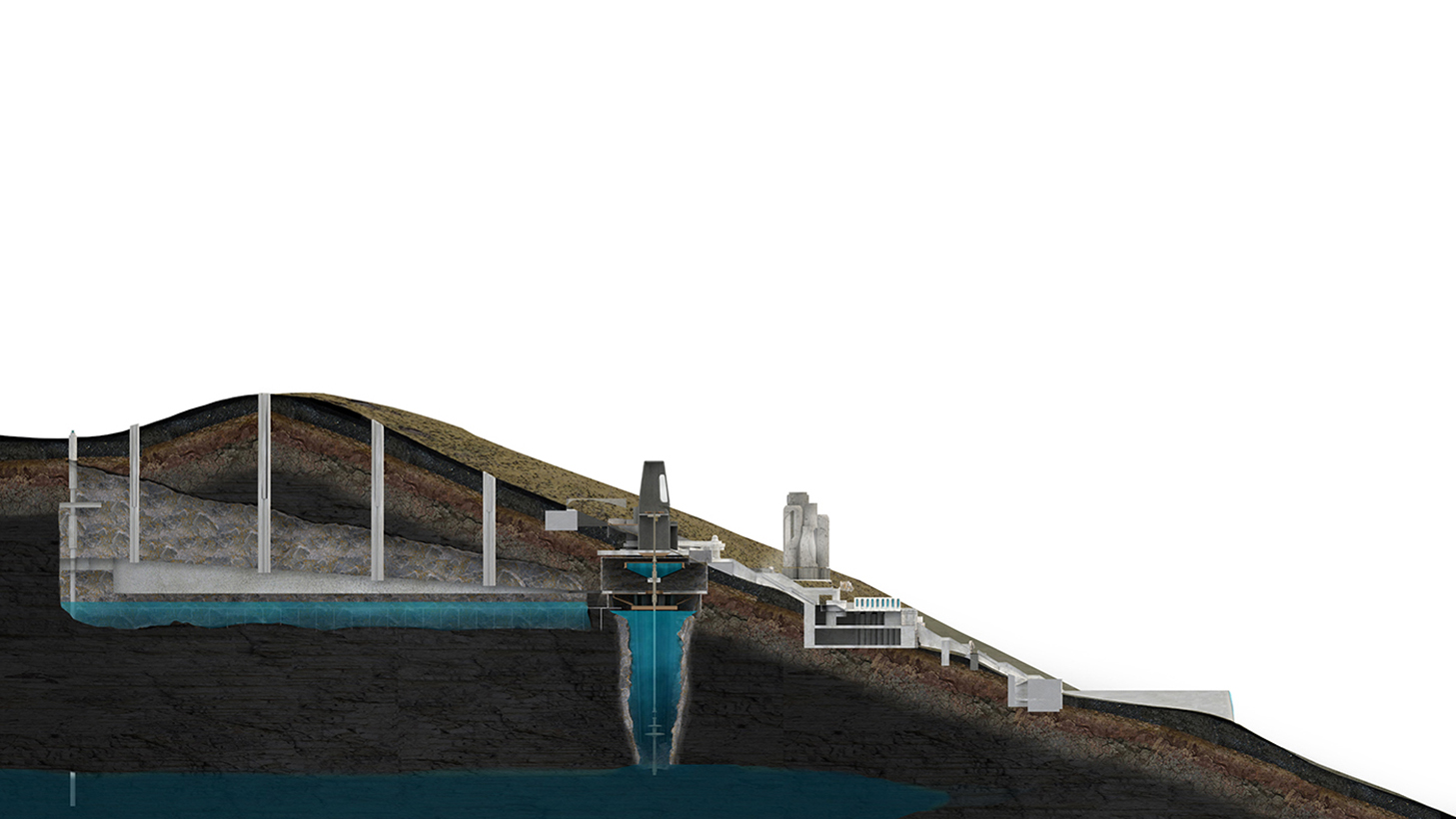

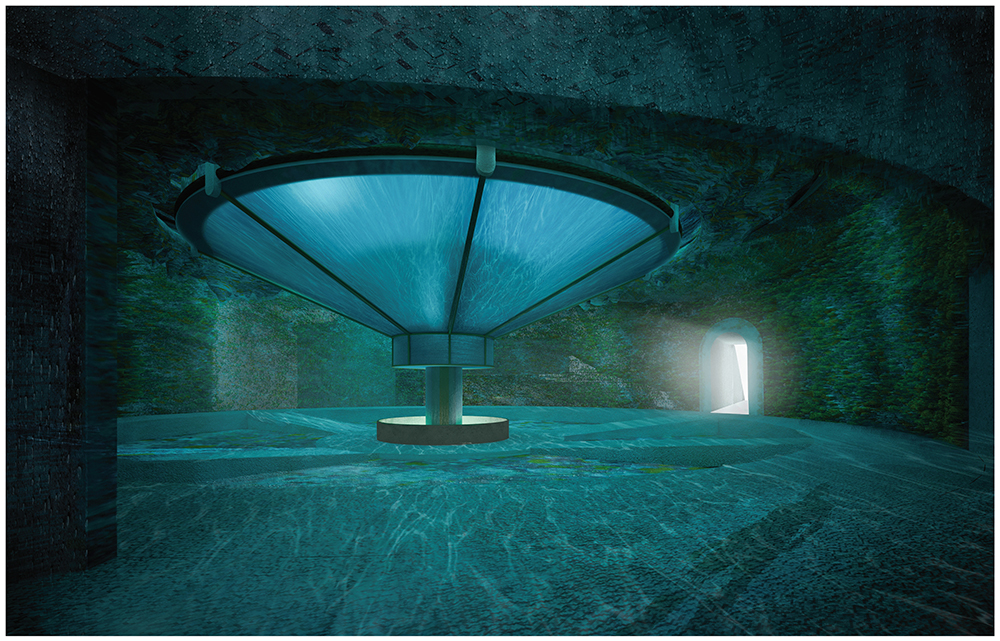

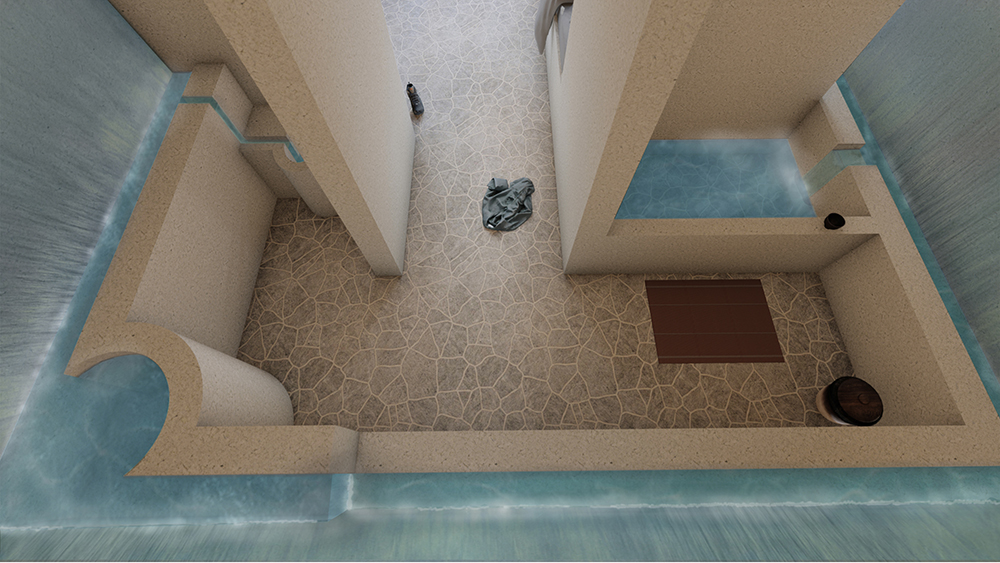

Indexing Water Resource Policy Retreat Center, Lhasa, Tibet

Future distribution of one-sixth of the world’s freshwater currently locked in Himalayan glaciers will inevitably be a primary focus of think tanks held at this Resource Policy Retreat Center. By conceptualizing freshwater as a hyperobject, a term coined by Timothy Morton and defined as something “massively distributed in space and time relative to humans” (Morton, 2013), we investigate the role that architecture plays in how thinkers engage with an entity that is beyond the scale and direct access of a group of twenty individuals. Does the presence and movement of the resource in question shape thought in new ways? Throughout the complex, water is active, breaking conventional functions of water and becoming “present at hand,” rather than a component of a scenic backdrop (Heidegger, 1927). The building’s machine-like aesthetic confronts false dichotomies of man and nature and positions human actions and systems as inseparable from surrounding ecosystems.

By aestheticizing the interactions between building and site, while utilizing the building as an index of freshwater ebb and flows, we argue that the idea that this site would otherwise be pristine or static “Nature” is false. Human presence on-site does not contaminate Nature, but it does shape new ecological interactions. The design pushes the experiential qualities of the building beyond visual perception and directly influence occupants by the climatic qualities of their contextual surroundings. By continuously changing the role of water, the architecture repositions the ways that visitors typically interact with water within a building, challenging scholars to think about the resource in new ways.

In collaboration with Brenna Thompson.

Periscope Microhouse Duplex, New Haven, CT